Surrealism Is 100. The World’s Still Surreal.

This is not an article. It’s a fish in the shape of a piano, floating in a clear blue sky, seen through a keyhole.

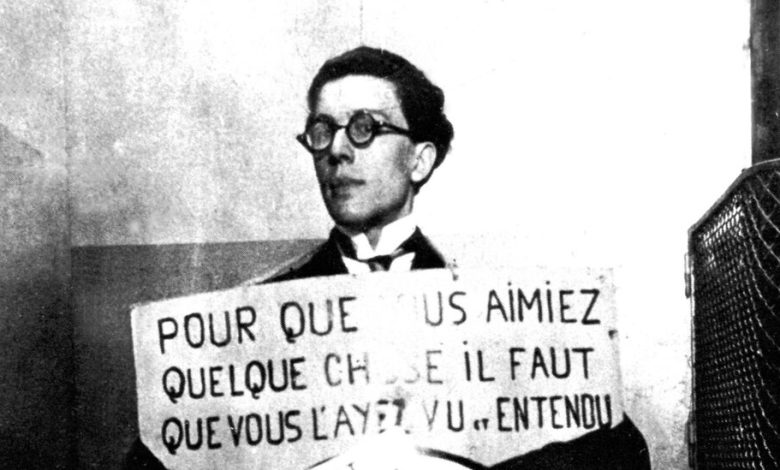

Surrealism, the art movement that gave us disembodied eyeballs, melting clocks and animals with mismatched parts, was born in 1924 when the French poet André Breton published a treatise decrying the vogue for realism and rationality.

Breton argued instead for embracing the “omnipotence of dreams” and exploring the unconscious and all that was “marvelous” in life. Art that could reach beyond the rational could liberate humanity, he felt. “The mere word ‘freedom’ is the only one that still excites me,” Breton wrote in his “Surrealist Manifesto.”

It was a literary idea that became an art movement and revolutionized nearly all forms of cultural production. It’s now commonplace to call pretty much any weird experience “surreal.”

A century later, what does Surrealism still have to offer us? Do its philosophical and political arguments have anything to say about contemporary life? Do we still, even in the faintest way, hear that Surrealist commandment: “Transform the world, change life”?

Museum directors, curators and art historians around the world will attempt to answer such questions this year, and Surrealism exhibitions will be everywhere, all at once. From Paris to Fort Worth, from Munich to Gainesville, Fla., and all the way to Shanghai, art institutions are mounting shows that explore the movement.