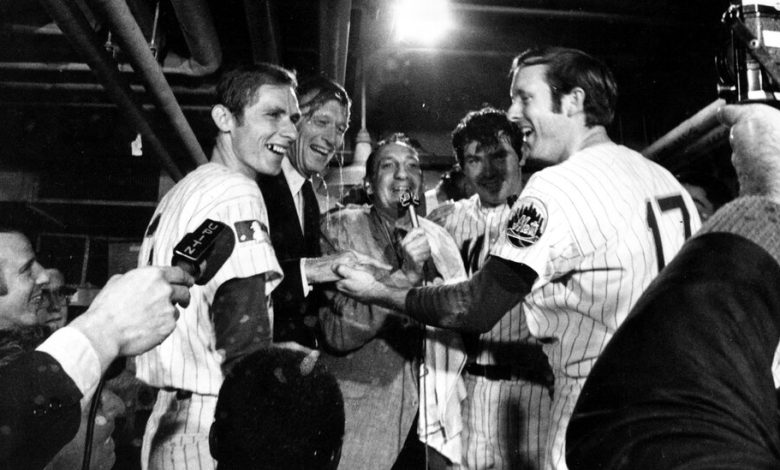

Bud Harrelson, Shortstop on Championship Mets Teams, Dies at 79

Bud Harrelson, the slick-fielding shortstop who helped take the Mets to their astonishing 1969 World Series championship and the 1973 National League pennant, and who remained in a Mets uniform as a coach in the 1980s and their manager in the early ’90s, died on Thursday in East Northport, N.Y., on Long Island. He was 79.

His death, at a hospice, was announced by Jay Horwitz, the Mets’ vice president of alumni relations. Harrelson learned in 2016 that he had Alzheimer’s disease.

Harrelson played in the major leagues for 16 seasons, 13 with the Mets; he appeared in 1,322 games with the team, the fourth most in franchise history. (Ed Kranepool tops the list with 1,853 games played, followed by David Wright and Jose Reyes.)

Standing 5 feet 10 inches and weighing between 145 and 155 pounds at varying times, he wasn’t much of a threat at the plate. He had a .236 career batting average and hit only seven home runs. But he possessed outstanding range in the field and a strong arm. He won a National League Gold Glove Award in 1971 for his fielding, appeared in two All-Star Games and was inducted into the Mets’ Hall of Fame in 1986.

Harrelson was signed by the Mets in June 1963, after starring at shortstop with San Francisco State University. After playing in the minors, he made his Mets debut in early September 1965.

He was remembered especially for a chaotic scene at Shea Stadium in Queens during Game 3 of the 1973 National League Championship Series between the Mets and the Cincinnati Reds.

After the Mets’ Jon Matlack shut out the Reds in Game 2, Harrelson told sportswriters that the team known as the Big Red Machine “looked like me hitting.” That quip found its way to the Reds star Pete Rose. Second baseman Joe Morgan, Rose’s teammate and fellow future Hall of Famer, warned Mets players that Rose had vowed revenge.

With the Mets ahead, 9-2, in the fifth inning of Game 3 and Rose on first base, Morgan hit a ground ball to first baseman John Milner, who threw to Harrelson in hopes of starting a double play. Just after Harrelson unleashed a return throw, Rose barreled into him.

“He hit me after the play was over,” Harrelson recalled in his memoir, “Turning Two” (2012), written with Phil Pepe. “I said something to him, cursed him. We were rolling around in the dirt and guys were pouring out of the dugout and out of the bullpens and little scuffles erupted all over the field.”

When play resumed, fans in the outfield stands threw debris at Rose, who was playing left field. There was no further scoring. The Reds captured Game 4, but the Mets won Game 5 and the N.L. pennant. They were defeated by the Oakland A’s in a seven-game World Series.

Harrelson was hampered by injuries later in his Mets career and was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies before the 1978 season. He concluded his playing career with the 1980 Texas Rangers.

Harrelson was named the Mets’ first-base coach in 1982 and later joined their television broadcasting crew. He managed in the Mets’ minor league system in 1984 and part of the 1985 season, then became the Mets’ third-base coach, replacing Bobby Valentine when Valentine left to manage the Texas Rangers.

Under manager Davey Johnson, the Mets returned to the World Series in 1986 against the Boston Red Sox.

In Game 6, at Shea Stadium, Boston was leading, 5-3, going into the bottom of the 10th inning and needed one more victory to win the World Series. But the Mets rallied. With two out, the score tied, 5-5, and Ray Knight on second base, Mookie Wilson hit a ground ball that went through the legs of the Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner, scoring Knight and winning the game.

“Knight came racing to third base and I not only waved him home, I accompanied him on his journey,” Harrelson recalled in his memoir. “I jumped up and started running. I had to slow down because I had Ray beat and I couldn’t touch home plate or get there before he did.”

The Mets went on to win Game 7 for their second and last World Series championship.

Harrelson succeeded Johnson as the Mets’ manager on May 29, 1990, and kept them in contention for postseason play until the last week of the regular season. But with the Mets headed for a fifth-place finish in the N.L. East in 1991, he was fired with a few games left in the season. He was later a scout and roving minor league instructor for the team.

Harrelson was an owner of the Long Island Ducks when the ball club, based in Central Islip in Suffolk County, began play in 2000 in the independent Atlantic League. He managed them in their first season, then became a coach and pitched batting practice.

Derrell McKinley Harrelson was born in Niles, Calif., about 24 miles southeast of Oakland, on June 6, 1944 (the date of the D-Day invasion), to Glenn and Rena Harrelson. His father was an auto mechanic and car salesman; his mother, Rena, worked in real estate. His brother, Dwayne, who was two years older, at first called him Bubba because he couldn’t pronounce brother; that evolved into Bud and eventually Buddy.

Harrelson’s first marriage ended in divorce. He is survived by his wife, Kim Battaglia; three daughters, Kimberly Psarras, Alexandra Abbatiello and Kassandra Harrelson; two sons, Timothy and Troy Harrelson; 10 grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

In May 2017, Art Shamsky, an outfielder with the Mets’ 1969 World Series champions, brought together his former teammates Harrelson, Jerry Koosman and Ron Swoboda for a visit with the Mets’ Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver, who was living with his wife, Nancy, in California’s Napa Valley and tending to his vineyard. Both Harrelson and Seaver were experiencing memory loss by then, Seaver as a consequence of having contracted Lyme disease. He would die of Lewy body dementia and complications of Covid-19 in2020at 75.

That reunion and the Mets’ 1969 season were recounted in “After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the ’69 Mets” (2019), written by Shamsky in collaboration with the sportswriter Erik Sherman, who had also been at the gathering.

“Nine years Tom and I were roommates,” Harrelson remarked at the reunion. “And we’ve been like brothers ever since.”

As Shamsky put it in telling of that trip, “It’s a cruel twist of fate what time has done to two men synonymous with everything great about the game of baseball — and the history of the New York Mets.”

Sofia Poznansky contributed reporting.